(This interview took place in Podcast Science episode#251. Une retranscription en français est également disponible)

Merci à Stéphanie et à Johan pour la transcription de l’interview.

Alan (A): For the first time since we launched the podcast almost 6 years ago, this episode is in English. And the reason for this is that we have an incredible guest live from the US: Carl Zimmer is with us tonight. And we are going to talk about viruses. This is March 1st, 2016. You are listening to episode 251 (yes, it’s a prime!) Welcome to Podcast Science !

A: My friend Karim and myself, have had the privilege of translating Carl Zimmer’s latest book into French, that is, the second edition of A Planet of Viruses. A fantastic book. Brilliantly written. And mind-blowing in that, your view of the world is bound to change once you’ve read it. So let’s have a quick look at who we have in our virtual studio tonight.

A: My friend Karim and myself, have had the privilege of translating Carl Zimmer’s latest book into French, that is, the second edition of A Planet of Viruses. A fantastic book. Brilliantly written. And mind-blowing in that, your view of the world is bound to change once you’ve read it. So let’s have a quick look at who we have in our virtual studio tonight.

- First, from somewhere in Connecticut, we have Carl Zimmer. Welcome Carl.

Carl Zimmer (CZ) : Thank you

A: And thank you ever so much for accepting our invitation.

We have 3 people in Paris : - Pierre, also known as Taupo, or @PierreKerner on Twitter.

Pierre (P): Hi everyone

A: Pierre is a great fan of parasites and the author of one of the best blogs in the World: Strange Stuff and Funky Things. Pierre has probably read everything Carl ever wrote and is his greatest ambassador in France

P: I’m so glad - A: Karim, my business partner, co-founder of Big Bang Science, also the author of another of the best blogs in the World, Sweet Random Science. Karim has helped us prepare this interview and he will keep an eye on the chatroom and relay the question to Carl when appropriate. Hi Karim, welcome

Karim (K): Hi everyone, nice to be with you.

A: A quick reminder to the chatroom, if you want your questions to be seen, please send them to @ps in the chatroom. - Last but not least in Paris, we also have Nico, insuring the broadcast and recording – and everything for this episode – works flawlessly. Hi Nico.

NicoTupe: Hi ! - A: In the suburbs of Lyon, France, we have David, from another Podcast in french called Lisez la science, which would translate roughly into “go and read your science”. David also helped us prepare this interview. Hi David, welcome.

David (D): Hi everyone.

A: This episode will be available as a podcast in the feed of both shows. There are probably more members of Podcast Science hiding in the virtual studio tonight but for some reasons there were not allowed to speak. - Finally I would like to mention our good friend Puyo, who will be with us in the chatroom, ready with his pencils for a live-sketching session.

So, Carl, before we begin this interview, I would like to let David introduce you to our French listeners. David ?

D: Carl, for this interview, I’ve been looking at your bio page and also your Wikipedia page in order to get some info about your career and about the books you wrote. I would like to share what I’ve learned with the audience. Stop me if I say anything wrong about you! Wikipedia reveals that you got a B.A. in English from Yale University before working at Discover in the late 80’s, first as a copy editor and fact checker, before becoming a contributing editor. I was stunned, regarding the quality of your productions and more specifically the book we are talking about today, to learn that your do not hold a B.A. or a Master’s Degree in science ! Because, dear listeners, it must be mentioned that Carl Zimmer is not your standard guest. Indeed, he is a columnist for the New York Times (not so bad), he is also present on radio shows such as Radiolab (I know Alan & Pierre love that podcast!), and some of his books have been widely acclaimed by the press and the science community: Soul Made Flesh – a History of Neuroscience – has, for example, been named one of the top 100 books of the year by The New York Times Book Review. “Science Ink: Tattoos of the Science Obsessed” has been featured in mainstream media such as the Huff Post, Der Spiegel or the Guardian. As a writer, the articles of Carl Zimmer, be they in Discover, The New York Times or on his blog, The Loom (now hosted by the National Geographic), have been recognized as some of the best American science writings in various anthologies. Carl also won the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Journalism Award three times for several of his articles. Now you might be able to grasp some of the reasons why we all consider that having Mr Carl Zimmer with us tonight is such an honor and we are happy to talk about his book A Planet of Viruses.

A: Thank you David. Enough introductions for now. Let’s begin the interview. Carl, for an immediate immersion, I would like to ask you a favour. Would you be OK with reading the first lines of the book aloud?

CZ: Sure. This is a book about viruses, but this introduction may not sound like it is a book about viruses; I am just trying to make the point that the viruses are everywhere on Earth, so I chose a pretty extreme place. So the book begins :

Fifty miles southeast of the Mexican city of Chihuahua is a dry, bare mountain range called Sierra de Naica. In 2000, miners worked their way down through a network of caves below the mountains. When they got a thousand feet underground, they found themselves in a place that seemed to belong to another world. They were standing in a chamber measuring thirty feet wide and ninety feet long. The ceiling, walls, and floor were lined with smooth-faced, translucent crystals of gypsum. Many caves contain crystals, but not like the ones in Sierra de Naica. They measured up to thirty-six feet long apiece and weighed as much as fifty-five tons. These were not crystals to hang from a necklace. These were crystals to climb like hills.

A: Wow, I think that’s exactly the voice I had in my head when I read it. Brilliant. I guess this will have given our listeners an idea of your style. Sharp. Straight to the point. And yet you manage to build unforgettable stories on the top of the bare facts. In less than a hundred pages, you tell us the history of the evolution of viruses, the history of our understanding of what they are – or rather our lack of understanding -, you cover influenza, HPV (which has to do cervical cancer and horned rabbits), you cover phages, marine viruses (now that’s a mind-blowing story, I hope we’ll manage to touch upon it!), endogenous retroviruses, HIV, Ebola, smallpox, giant viruses, and many more. You even cover the definition of life itself! We’re all trying to be good science communicators here, but I must confess, we still have a long way to go before we master this art as brilliantly as you do. Anyway… The book begins with the story of our understanding of what viruses are. We’ve known them for centuries, mainly through the symptoms they put us through. But it’s only quite recently that we’ve started to understand what they actually are. Can you start by telling us that story?

CZ: Yes, so, people were becoming sick from viruses obviously for as long as there have been people, and even before, but it was never clear what was making them sick. And people would learn certain ways to deal with viruses, like you know, trying to avoid infections. People with smallpox, they had to be isolated from other people. And then even vaccines were developed before people knew what viruses were. It wasn’t until the late 1800 that researchers were trying to understand why some tobacco plants were getting sick and they thought maybe it was bacteria. So what they did was that they mashed up the tobacco leaves into a kind of a fluid and then passed it through filters and what they discovered was that they could actually pass it through filters that would trap bacteria, these are incredibly fine filters, they just had what looked like a clear fluid and this could still infect tobacco plants. And so, that was when this mysterious substance was called viruses.

A: Virus, which has a double meaning, doesn’t it ?

CZ: Yeah, it can mean poison or seed. And I love that, sort of, double-meaning of it, because viruses, they really are kind of like seeds. There are these shells of proteins with genes inside of them that can make new viruses, but you know, to us they can be quite poisonous.

A: Yeah. So I think it was in 1923 that a British virologist declared that it is impossible to define their nature, and the New York Times a few years later titled that the old distinction between death and life loses some of its validity ?

CZ: Yeah this was because, you know, the problem was that scientists had discovered viruses. They showed that there was something that was incredibly tiny that could cause disease but they couldn’t see it because microscopes weren’t powerful enough and so then what some researchers did, Wendell Stanley that chemist in particular, what he did was, he said, well maybe I can crystalize viruses, maybe I can see them by crystallizing them. The same way you can try to crystalize salt out of salt water. So he actually managed to do that with these viruses that infected tobacco plants. And so he could actually create these crystals of viruses and it was very strange because you could just put these crystals away for months and then take them off the shelves and put them in water and then they could cause diseases again. So people were very confused, like, what are these things ? Are they alive or are they not ? And I think we’re still debating that today.

A: Okay and it wasn’t until the end of the 1930s that we were actually able to see them.

CZ: Yeah that’s right, then finally there were microscopes invented, electronic microscopes, that were powerful enough to give scientists the opportunity to zoom in and actually see these things, because they are hundreds of time smaller than bacteria. And actually scientists were able to see the viruses that infect bacteria, what they called phages. And so at last they could actually understand that these viruses, they are very small but they are not invisible, they are tiny little entities that can invade our cells and basically force those cells to make new viruses.

A: Karim? Do we have questions in the chatroom already?

K: Well so far we do have one question actually, it is a question from Haeckel I think, asking, she is not sure but, do prions have a similar story of discovery?

CZ: Hum, yeah it’s interesting, so prions are just proteins which have a deformed shape, and what they can then do is they can grab on to other proteins and deform them as well. And so that change in shape can sort of spread out among these particular proteins. And then they can cause diseases like mad cow disease, other kind of diseases. And certainly there was a lot of debate about certain kinds of diseases, researchers just couldn’t find bacteria or viruses to account for it. And eventually Stanley Prusiner, University of California in San Francisco, was able to isolate them and find evidence that it was actually these, what he called prions, particular kind of proteins that began to form this way. So yes there is an interesting parallel in that story.

K: Thank you.

A: Thank you very much! Let’s move on to our first virus, can you tell us a little bit about the rhinovirus?

CZ: So the rhinovirus in English, we call it “cold”, and my poor French makes me forget what it is that is in French.

A: Rhume.

CZ: Rhume, yes. So basically, rhume, or the cold, this is a virus that we’ve all had. It doesn’t make us particularly sick for most people, but you do get sick for a few days. You know, there are records about colds and treating colds going back thousands of years, actually, to earliest written records about medicine. Well it wasn’t actually until the early 1900’s that scientists were able to show that these colds were being caused by particular viruses. There was a scientist who took the mucus from his sick research assistant and students and filtered it through and then basically gave other people colds! That was the kind of test that you needed to show that this was in fact a virus that was causing colds.

A: Yeah, I remember that bit in the book, it is absolutely disgusting… It was Walther Kruze in Germany. Interesting fact, you mentioned that the virus, well, the cold, was called « resh » in, … I don’t know what language that would be, was mentioned 3500 years ago in the « Ebers Papyrus ».

CZ: Yes that’s right.

A: It’s really be annoying us for like… Forever! It’s only now that we’ve discovered what it is, and we still don’t have a cure for it, do we?

CZ: No we really don’t, you know, there are some studies that suggest that zinc might be able to shorten the span of a cold but it’s not really a cure. And there is really no way to prevent them. And so, there is actually a lot of debate about what we should do about colds. Lots of people say : “Look, for the most part, they’re not that bad”, and there is even some indication that maybe getting colds as a child might actually help the immune system, these are just suggestive studies. On the other hand, people are starting to appreciate that cold viruses can actually cause more harm than was previously thought. So you know, most of us get these colds and they make us feel lousy for two or three days and that’s it. But it turns out that colds can sometimes cause more serious respiratory infections and can trigger other kinds of infections, they may be associated with asthma for example. So we may need to take them more seriously. We’ve only started to appreciate these rhinoviruses, because you can actually now look at the genetics sequences in them and so scientists can actually see them showing up in lots of different cases where they weren’t expecting them. So our fight with the cold continues after thousands of years.

A: No but in the book you say that if we knew how to get rid of it, it might not be a good idea.

CZ: Yeah that’s right, I mean, in a way, it’s possible that getting a cold might be kind of like being exposed to bacteria, dirt and so on, that it is a way for the immune system to be trained, to be able to do a better job of finding pathogens without overreacting. We don’t want the immune system to respond to harmless things, because then you can maybe develop allergies, or an immune disorder and so on. So, there are intriguing studies in that direction, I wouldn’t say that they definitely show that getting a cold is a good thing, but it’s interesting to think about.

A: Yeah, the conclusion of the chapter is that we maybe should think of them not as ancient enemies, speaking about the rhinoviruses, but as wise old tutors?

CZ: Yeah, I mean, viruses, we think of them just as enemies and I think that we really need to broaden our view of them. They can have many different roles; there are certainly some viruses that are just bad, just all out bad. Then there are other viruses that might be actually quite harmless and other viruses that may actually believe it or not be beneficial. So we need to just consider all those things.

A: Okay. Karim, do we have any questions for Carl regarding the rhinovirus?

K: Not exactly the rhinovirus but we do have a few questions if I can go ahead. First one: Did you come across some cool tattoos of viruses when you were researching for “Science Ink” ? And if you could you give us some examples?

CZ: [laughs] So this is referring to this book I called “Science Ink: Tattoos of the Science Obsessed” and I discovered that a lot of scientists had tattoos and they weren’t sharing them with anyone, and I coaxed them to show me their ink. Yes, let’s say the one that comes to mind is actually one of these viruses that infects bacteria called phage, and there are some phages that are just perfect for tattoos because they look like some weird attack-robot from The Matrix, they’re all sort of hexagonal and have these, like, sort of pointed legs on them, and they land on cells and they drill in this syringe and pump in their genes. They are really bizarre so yeah I have more than one phage tattoo in my collection.

K: Excellent, thank you! Do we have time for another question?

P: I would like to say that one of my co-workers is actually pictured in that book, she has this sort of butterfly made of Darwin’s finches beaks.

CZ: Oh yeah!

A: I remember!

P: So she says “hi!”. [laughters]

CZ: That is a beautiful tattoo.

P: Yeah it was.

A: Karim another question?

K: Yeah, we have one question from Alex asking if viruses fall under the strict definition of being parasites?

CZ: Hum, yeah most of them I would say, well I don’t know, again, it’s a tough question. Viruses kind of defy easy categories, the more you look at them. A flu virus, it’s hard to see that as anything but a parasite. It’s something that thrives at its host’s expense and that’s pretty much your definition of a parasite. But then there are other viruses that have actually beneficial relationships with their host, so you know there are viruses that for example carry genes for antibiotic resistance. When viruses like that infect bacteria that lives inside of us, and we take antibiotics, the bacteria is going to survive because it has these genes that were brought to it by the viruses, so the bacteria survives and reproduces and the viruses are able to reproduce inside of it. So that’s not a parasite. There is a whole spectrum of relationships that viruses can have to their host or to other species. We have the viruses that are parasites to bacteria in our gut, they might actually be good for us, because they keep our bacterial ecology in balance, so for us, we wouldn’t call them parasites, we are glad to have them to stay healthy perhaps. An answer to that question is harder to give than it might seem.

CZ: Hum, yeah most of them I would say, well I don’t know, again, it’s a tough question. Viruses kind of defy easy categories, the more you look at them. A flu virus, it’s hard to see that as anything but a parasite. It’s something that thrives at its host’s expense and that’s pretty much your definition of a parasite. But then there are other viruses that have actually beneficial relationships with their host, so you know there are viruses that for example carry genes for antibiotic resistance. When viruses like that infect bacteria that lives inside of us, and we take antibiotics, the bacteria is going to survive because it has these genes that were brought to it by the viruses, so the bacteria survives and reproduces and the viruses are able to reproduce inside of it. So that’s not a parasite. There is a whole spectrum of relationships that viruses can have to their host or to other species. We have the viruses that are parasites to bacteria in our gut, they might actually be good for us, because they keep our bacterial ecology in balance, so for us, we wouldn’t call them parasites, we are glad to have them to stay healthy perhaps. An answer to that question is harder to give than it might seem.

K: Well great thank you. There already answers some of the other questions we had. Some people are asking if viruses could be useful for human beings.

CZ: Yeah viruses can be useful in very many different ways to humans, both just in a sort of physical or medical way but also, you know, we use viruses for lots of applications as well, so viruses are great resources.

K: Ok thanks.

P: Someone asks if they can be considered as symbionts? Of sort?

CZ: Yeah, well, I guess it depends on how you define a symbionts. If they are talking about things that have a mutually beneficial relationship with their host, sometimes yes. For some species of viruses, for some hosts, it can actually be beneficial, they can bring beneficial genes and so on. Sometimes it’s just kind of a conditional thing, sometimes viruses basically have the attitude towards their host of : “we can be friends, until things get bad and then I don’t want to have anything to do with you”. So viruses can invade a cell and sit there very quietly and not cause any harm. But then if the cell experiences a stress, the virus can detect the stress and it can switch on its genes, make lots of new viruses and rip the cell open and escape. So the cell dies and the virus is able to get out of there, because it is a bad place to be.

A: Thank you. Time flies so I’d like to jump to the next chapter. We’re not going to go into the details of each chapter but I think it’s worth spending a minute or two on influenza. What makes it so particular ? So maybe first you can tell us where it comes from ? I mean, originates from?

A: Thank you. Time flies so I’d like to jump to the next chapter. We’re not going to go into the details of each chapter but I think it’s worth spending a minute or two on influenza. What makes it so particular ? So maybe first you can tell us where it comes from ? I mean, originates from?

CZ: Yes, so flu viruses have a particular origin: They come from birds, particularly waterfowls. Birds have a huge diversity of flu viruses that live in their guts, and for the most part they are harmless. Then, on a regular basis, new bird flus jump into our species. They adapt to circulating among humans, and instead of being a gut virus they become a lung virus and we spread them by sneezing and getting the viruses on our hands and contact with surfaces and so on. We’re constantly getting this replenished supply of flu viruses, really, just all the time. Which is different than how other viruses originate.

A: And throughout history it has been an awful killer hasn’t it? You mention the 1918 outbreak, which infected half a billion people and killed an estimated 50 million?

CZ: Right, it might have been more than half a billion people, it’s hard to know precisely how many people were infected but what’s amazing it’s that it spread all over the World, to even the most remote Alaskan villages; it was a worldwide outbreak, and quite catastrophic.

A: Karim do we have any questions so far?

K: There is one question which is at the heart of the book, I think: It’s weather or not viruses are alive?

CZ: I get asked this question all the time, but I always feel like: before I have to answer that question, I think the questioner needs to tell me what life is. [laughs] You know, define life for me, because if you actually look for definitions of life there are hundreds of them that are “in circulation” among scientists. There is no clearly accepted definition of life. People will say : “well living things have this list of qualities” and they gather up some arbitrary list and it’s a different list depending on who you’re talking to. So it’s a difficult question to answer because the terms are so contentious. There are certainly features of living things that most viruses don’t have. Maybe the key thing is that our cells have little factories for building proteins out of building boxes, they’re called ribosomes. Our cells can grow, they can build new proteins, they can build their own genes. Viruses can’t do that; they don’t have that capacity. So if that’s your definition then, yes, I would say they are not fully alive. Although there are some viruses that seem to be getting right close to that kind of capacity, they are called giant viruses. And they are so much like utterly alive that some people are saying that they are not sure whether they are viruses or not; it gets confusing. I think that we tend to think of life in a very binary way, life and death, but I think that in terms of biology, there is actually a spectrum, I don’t know how to call it, biological systems, living systems, from the simple virus to the full-blown living thing like us. I think that it’s actually harder than you think to draw a line and say “on this side things are alive, on this side things are not”.

A: I’d like to go onto the next chapter which is about HPV, the Human Papilloma Virus. Which can cause rabbits to grow horns (that’s an incredible story!), and Human beings to get cervical cancer, or even look like trees. Can you share your insight about this one?

CZ : Sure, so HPV is one of the better known viruses now, I think partly because their threat is so well appreciated. Women who are infected with certain strains of HPV are at risk of developing cervical cancer. Men can also develop cancers as well from this virus. What happens is that the virus gets into cells and it can indifferently speed up their replication and then kind of gets out of control, and the cells are just turning into cancerous tumors. Their runaway growth becomes very dangerous. How they were discovered is pretty amazing because it was in the early 1900’s, in the United States, people would talk about these rabbits that grew horns and it seemed like mythology ,but every now and then people would actually find these rabbits! A researcher at Rockefeller University named Richard Shope in the 1930s, asked a friend to go hunting for these rabbits and ship their bodies back to him. He studied these horns and he realized that they were actually like cancerous growths. And then when he studied them closer he was actually able to isolate viruses out of them and he could use those viruses to cause new horns grow in other rabbits. So papilloma viruses are found basically on every mammal on earth. HPV in particular infect us, this is actually a real success story in term of virology, because here we have a way to eliminate cancer, a huge amount of cancers, because there is an effective vaccine against HPV. If you get people HPV vaccines you’re not going to get this kind of cancer. This is a cancer that affects many thousands people every year. This is a kind of cancer we can just eliminate, and you can’t say that about other forms of cancer. The HPV vaccine results are starting to come back in; the long term data is showing that this vaccine is really starting to drive down the rates, in the USA at least, of cancer-causing strains.

A: Karim, any questions?

K: Not about the rabbits I’m afraid.

A: But lots of comments on this in the chatroom.

P: You haven’t talked about the jackalope myth though and the link between the cottontail rabbit virus and this myth.

CZ: Yes, right, so people would refer to these rabbits with horns as jackalopes, so I guess it’s like a pun on “jack rabbits” and “antelopes”. I remember the first time, when I was young, I went out to Wyoming and Montana, if you went to a restaurant, you would sometimes see jackalope heads on the walls, which were actually like rabbits with antelope horns glued onto them. And you could buy postcards with jackalopes, and so on, and I just assumed that it was just a myth that Westerners would use to fool Easterners about the West of the US, but it turns out that it actually has a little grain of truth in it. That there really are these rabbits with horns.

P: I’ve just posted a picture of Ronald Reagan carrying a jackalope trophy.

A: And there has been another picture in the chatroom, I was going to skip the question but since it’s been mentioned, could you tell us the story of Dede, the Indonesian boy in the 80s?

CZ: Yeah, so in addition to cervical cancer, HPV, in other situations, can cause this kind of runaway-growths in skin cells and that can lead to warts for example, and other kinds of pre-cancerous growths. Part of the reason why these things happen is that the cells get ahead of the immune system. The immune system can keep these viruses in check, you know most of us actually have HPV infections, just on our skin, but they are pretty much harmless. They are not the cancer-causing strains that cause cervical cancer. But in any case, there was this man who probably had some type of immune deficiency which means that as soon as he got HPV on his skin, it would just take off. It would just make his skin cells grow really fast and it’s horrific that his skin did look like tree bark. He would grow these huge growths on his arms and other parts of his body. He was found by doctors in a traveling freak show, and they did really extensive surgery to remove these growths and he looked normal again but these things just come right back. Because HPV is just everywhere and it is very hard to avoid it and so he would inevitably pick it up and without an immune system to defend himself from it, he just becomes this tree-man again.

A: Sad story. Let’s move on to the next chapter. It’s about phages, amazing little things. So you’ve already said a word about them, could they be a solution to the growing bacterial resistance to antibiotics?

CZ: Right, so phages are basically any kind of virus that infects bacteria and they are incredibly abundant because there are so many bacteria. The most abundant kind of phages are therefore ocean phages because the oceans are so big and they are so full of bacteria. Scientists have tried to come with estimates for how many there are: By one estimate it might be 1031, that’s a 1 with 31 zeros after that. This is a lot of viruses. I mean, basically viruses are the most abundant life form, if you can call them that, in the World. We can really benefit by studying phages in particular for a lot of different reasons. One reason is that there are phages that specialize in infecting the bacteria that infect us. So if you have a wound that gets infected by bacteria, it’s possible to use phages to clear-up that infection. In France a hundred years ago, this so-called “phage-therapy” was invented and became very well established, before being replaced by antibiotics. And now that antibiotics are starting to really falter, we’re starting to see antibiotics resistance and so on, people are increasingly turning their attention back to phages, seeing if they can introduce phages that would reliably get rid of infections.

A: You’ve mentioned the marine viruses, I would like to stay there for a little while. I discovered something incredible while I was reading your book, if you breathe ten times, one of those breaths is due to a virus?

CZ: Yeah, it’s kind of mind-blowing actually that there are viruses, phages, that lives in the oceans that specialize in infecting the bacteria that produce a lot of our oxygen. These viruses carry around with them some of the genes for photosynthesis. What happens is that they go into bacteria and they essentially can replace the host photosynthesis genes with their own. That’s because that makes the host better at producing the kind of building blocks they need to build new viruses. They are sort of tweaking the photosynthesis to suit themselves and in the process, these cells are taking in carbon dioxide and they are giving off oxygen. We’re breathing that oxygen, and that oxygen, in a huge amount of cases was actually brought to us by these infected bacteria. So literally we have viruses to thank for a lot of the oxygen we breathe!

A: That’s really an amazing story.

CZ: Yeah!

A: Another amazing story can be found in the chapter called “Our Inner Parasites”, that’s where we learn that mammals have viruses to thank for the very existence of the placenta?

CZ: Yeah so, in this part of the book I talk about certain kinds of viruses that, basically, become part of our genome, we actually pass down their DNA with the rest of our own DNA, they blur themselves with us. I have been fascinated with these kinds of viruses for a long time and I’ve kept up with all the researches that have been going on with them. Scientists are finding that in several cases, their DNA, which has been passed down through millions of years, has been harnessed through evolution to do things for us. In the placenta for example, placenta cells will use a gene from viruses to make a protein that helps them to build connections between each other, between the cells and the placenta. This is essential, so when scientists take a mouse and knock out this virus-gene they can’t make placenta and the embryos die. It’s just a really striking example of how we have , sort of, co-opted viruses. Ironically we use their genes also to fight other viruses. We are part virus, as strange as it may seem.

A: Yeah, I think we officially have mind-blown people in the chatroom right know. [laughters] Karim anything to add? Any question?

K: No questions but yeah people are reacting and saying how amazed they are and realizing how important viruses are. And actually I had a question if I may, do you think phage therapy will be used in the future?

CZ: Well phages therapy is actually being used now, just not very widely. It’s being used, I believe. There is a test going now in Belgium, I believe. A really important test, I believe that there it’s being used on burn victims. What’s happening is that scientists are developing ways to use them in places where antibiotics are failing the most. For burn victims, you don’t want to put people on lots and lots and lots of antibiotics when they are so vulnerable. So phages might be a much safer alternative for them. But the real question is how reliable will phage therapies be. You can’t just pick up any phage to fight a particular infection, one species of virus may only infect one species, or even one strain of bacteria. So unless you’ve got the right match, it just may not work.

K: Thank you!

A: There are a couple of chapters in the book dedicated to the HIV, which I don’t think we have time enough right now to go through, so I strongly invite the readers to read your book, either in English or in French, to discover the full story, which is kind of mind-blowing as well. You also share the story of the globalization of the West Nile virus, and how it became American, so we’re not going to go into the details of that story either, but I guess the same kind of phenomenon is happening right now with the zika virus ? [Zeekah] ? How do you say that in English ? It is [zeekah]?

CZ : I’ve heard it’s pronounced [zeekah].

A : [Zeekah] sorry.

CZ: We can track viruses these days in a way that just wasn’t possible in earlier decades or centuries so what we’re finding is that there are some viruses that show up in one part of the World and then sooner or later in another part of the World. It’s quite remarkable to watch them basically marching along, so zika virus was found in Uganda I believe in the mid 1900, and it really wasn’t found in many other places until the past couple of decades. Then it started showing up in places like Polynesia, and actually only last year did it finally arrive in the Western hemisphere; in Brazil and now it’s just been spreading incredibly rapidly into other parts of the Americas. This is a pattern we’re seeing again and again. West Nile virus was limited to Africa and Asia until about a decade ago, well, over a decade ago. Then it was said it was in New York City. We knew about it because birds were dying, it affects people and birds so actually birds in and around the Bronx zoo were dying, scientists looked at them and discovered there were these viruses in them. Just there in New York ! They probably got carried over in mosquitoes from some other part of the World. And that’s all it took for it to shoot out across the whole country, and so West Nile virus is just a regular fact of life in the United States now. There’s no way we’re going to get rid of it. People die of it every year now and we have just had to resign ourselves to that. And so zika may become one of those things unless we can get a vaccine and really like do an aggressive campaign against it and the mosquitoes that carry it. Chikungunya is another example too, unfortunately we’re seeing more and more examples of viruses shooting out all over the world.

A: Yeah, speaking about terrifying stuff, you also have a chapter dedicated to Ebola. We are not going to develop it here. You have written a chapter about Smallpox. I would like to stop a little longer on this one. I’m guessing people my age and younger will also have a shock when reading this chapter. I was born in the early 70s in Switzerland and until I read this story, I had never actually realized how murderous smallpox had been for the previous thousands of years and how amazingly incredible it is, that we managed to eradicate it (and yet still managed to sequence its genome). This is a fantastic story, which even covers the very invention of vaccination. Can you tell us all there is to know about smallpox? In like 5 minutes?

CZ: Yeah, right. I can certainly, you know, hit some of the high points. I mean the story of smallpox is really unbelievable. It is hard even to believe it because, it is not around now. This is actually… This was maybe the worst of all viruses and we beat it. Hehe. And that should give us some confidence in trying to go after some of these other viruses. This was a virus that spread from person to person. It causes horrible scarring and it was incredibly lethal, you know: A sizable fraction of people who get it die. There is one estimate that in Europe, Europe alone, between 1400 and 1800, smallpox was killing 500 millions people every century. It is just unconceivable to imagine, but people developed ways of what we would call now vaccinating against it. Actually, it probably started in China, and then was brought to Europe and then Edward Jenner, in the 1700’s sort of improved on it by finding a strain of virus that could protect you against smallpox without being so dangerous itself. But it was not until the 1950’s, 1960’s that people actually started talking about eradicating the virus altogether and then actually started an eradication campaign. And finally in 1977 was the last case in Ethiopia, the last in-the-wild kind of case of smallpox. We still have smallpox around. As far as we know, it is only in a couple of laboratories, one in United States and one in Russia. And that’s it. And so now the debate is wether we should get rid of it altogether or hold on to it to study for their insights.

A: You nailed it, in less than 5 minutes. That’s absolutely amazing, thank you so much. Karim, do we have questions ?

K: There is a vocabulary question. Is there a “bigpox”?

CZ: [Laugh] Not that I know of. There are giant viruses, and I write about them in the book. These are viruses that are as big as bacteria. Hundreds of times bigger than previously known viruses with sometimes a couple thousands genes, which is crazy, because most viruses have only ten genes or less. But no, I haven’t heard of a bigpox. Smallpox is bad enough.

K: And also, I just wanted to know: You said that the smallpox virus was kept in a safe. Where do you stand ? Do you think we should destroy it or keep on searching ?

CZ: Well… I think that there are very good arguments that have been made on both sides but the fact that eradication is permanent makes me kind of a little leery about that. And actually, you could even argue that maybe eradication is not even possible. For example we are not 100% sure that all the smallpox stocks have been accounted for. It is possible that some people are holding on to them somewhere and they are going to unleash them. We just do not know. The other thing is that we know the smallpox genome. We know the sequence of genes that make smallpox smallpox. And in this day and age, if you know the genetic sequence of a virus, you can make the virus. With synthetic biology, I don’t think that smallpox will ever be eradicated. And there is still a lot that we still do not know about smallpox. And there is a lot we do not know about the relatives of smallpox, which could also cause the next big outbreak so… I tend to lean on not eradicating it.

A: Ok, thank you very much. You mentioned giant viruses a minute ago. I think Pierre has a question for you linked to recent news. Pierre ?

P: Yes indeed. I came across your coverage of a very recent discovery regarding giant viruses: A CRISPR-like system found in a giant virus. I was wondering whether you could explain in a few words what the discovery is about, but also, what kind of precautions you take when writing about such recent discoveries and hot topics?

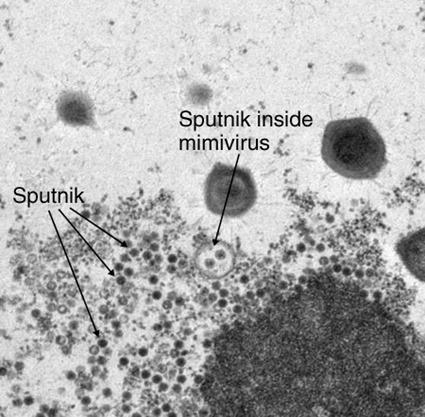

CZ: Right. So I write about giant viruses in “A Planet of Viruses”. But the science of giant viruses is moving so fast that there are just things that you just have to report on in addition to it. This is something that I actually wrote about just yesterday on the website STAT. There I reported on this puzzling finding: there are giant viruses that actually can get infected by their own viruses. Believe it or not, there are viruses of viruses. You have giant viruses that infect protozoans and then there are these other viruses, these little viruses called virophages that infect the giant viruses. And what scientists found was that there were some of these virophages that could infect some giant viruses but they could not infect a closely related strains of viruses. And they thought “What’s going on? They should be able to do this”. It seems that the giant viruses have some kind of defense against them. It is strange enough that viruses can have their own viruses, it is really weird to think that viruses can have their own immune system. What scientists are now proposing, based on their studies of these viruses, is that these giant viruses are actually able to capture little bits of DNA from the virophages and use that to basically recognize them when they invade and use enzymes to chop them up. And if it is true, it is actually very similar to what happen in this thing called CRISPR, which is an immune system that bacteria use to fight viruses. CRISPR has gotten very famous in the past years or so because scientists have adapted it to edit genes and it is very powerful, very fast, very accurate, very cheap and it is opening all sort of exciting and scary possibilities. It turns out that giant viruses might have a kind of CRISPR of their own. Who knows if that could lead to some of other kind of editing applications. We really don’t know right now! You raised a good questions about when things like that happen: A new paper comes out with really wild findings. You have to be careful because it may very well turn out not to be true. Maybe in a year, or two, or three, scientists trying to follow up on it just realize that the original scientists got it wrong. I think you that you just need to bear that in mind as you are writing about it and talk to outside experts, people who might be a little skeptical, and try to include those voices in your pieces when you can. It is a wonderful idea and I think we are going to have to wait and see in the next year or two whether it really holds up for the scrutiny.

P: So is that what you did when you reached out for Jennifer Doudna, for this particular story, did you reach out to her to get her opinion about that?

CZ: Yes, I contacted Jennifer Doudna at Berkeley who is an expert on CRISPR, talked to a couple of virologists as well, just to kind of get their sense of it. I think that for one thing people recognize that the authors of this new study are the World experts on giant viruses, these are the people who discovered giant viruses. Didier Raoult and others in France who really have pioneered this whole field. If they are going to publish a paper, you’re going to give it some serious attention. That doesn’t mean it necessarily true, but it does count for something.

A: Thank you so much. Time flies, we have to wrap it up as far as the book is concerned. There is one last question regarding the book I would like to ask you: basically, it’s just a matter of time before the next viral plague hits us, isn’t it?

CZ: Yes. Unfortunately. We’re dealing right now with zika in the Americas for example, they’re happening all the time, it’s a question of just the scale of them. Sometimes they turn out to be new viruses that are not especially huge. So right now MERS for example, which I write about in the book. You don’t want to get it, it can be quite lethal, but it seems right now to be fairly limited and to be spreading in hospitals, and not really going out beyond that, so it’s not like the flu. But yeah, we will have more of these and some of them could be quite bad, I can’t say what it will be next, I mean, it could a new flu pandemic, it could be a new strain of bird flu that turns out to be very fast-spreading and also relatively deadly. There are lots of things we can do to get ready for these things, that’s good, but it’s also frustrating because you can see how we are not doing what we could do. With the ebola outbreak for example, why was it that we didn’t have an ebola-vaccine ready to go? I mean, there were good results on Ebola vaccines researches years ago ! But the researchers just couldn’t get anybody to get along and really do the research on it. So we need to be better at preparing for that next virus outbreak.

A: That’s a good message, thank you so much. Karim any questions?

K: No, I think people are still amazed and trying to process the “virus within the virus” thing.

A: Ok, so regarding the book, I definitely invite our listeners to read it, either in English, it’s called “A Planet of Viruses“, and the second edition is available everywhere. And as of 11 March it is also available is French under the title “Planète de virus“. Am I not sure I mentioned it, but the translators have done an amazing job. Now I would like to let David and Pierre ask a few more questions, not about about the book but about you, life and everything, your writing especially. David?

D: I would like to come back to your academic background: Does one not have to be a scientist to understand and communicate science?

CZ: I hope not, because I’m not a scientist! So if that were true, I would be out of a job. No I mean, certainly, being a scientist gives you a lot of great insight into how science works and it gives you a lot of expertise in a particular field, but I don’t think that that prevents other people from learning about science, or writing about it, and so on. I would say that non-scientist have to recognize that it can be complicated and that it takes time to really understand it. It’s very easy to sort of go into things with the wrong assumptions. Certainly I as a non scientist, I am constantly questioning myself, double-checking to make sure that I have things right, that’s fine and it’s interesting to learn how I’ve made mistakes and to learn from them. I just don’t like to… I prefer to discover those things before stories go to print rather than afterwards.

A: I guess that’s good advice! David I think you had another question?

D: In the foreword, we can read that the contents of the book were originally intended as essays for the World of Viruses project http://worldofviruses.unl.edu. Could you please give us some insight about this initiative, its status, and how the book came to like perhaps?

CZ: Right, so this was an educational project that was organized by some folks at the University of Nebraska, they do a lot of different educational projects on evolution and other subjects, and they got in touch with me, to see, at first if I would just write a few essays about viruses just to introduce them to students and so on. And I just started writing them and then after a while we all realized that I had almost accidentally written a book. The University of Chicago Press got interested and so I went back and reworked all the essays to really make them unified and actually hang together as a book. So this became one of the things to emerge from this project. They have done other things, comic books, radio programs, all sorts of posters, all sorts of different interesting things. It was a lot of fun to be working with them and seeing people taking viruses in different creative directions.

A: Pierre? You also had a couple of questions?

P: Yes indeed! If we have a little time left, I’d like to ask you a bit more about your different works and experience in science outreach. For many, us included, you’ve reached a very nice balance in your delivery of facts, storytelling and opinions. What would you consider were the major breakthroughs that enabled you to reach that balance?

CZ: Well, I mean, my own experience, I can’t say that it was all carefully like thought out but you know… I worked for ten years at Discover Magazine, I was a senior editor there for four years and that was really my education in science journalism, to really learn how to do it, starting as a fact-checker and then writing short pieces and so on, and learning from some really talented editors and journalists. Since then, I’ve basically been writing on my own full time and I would just like to seek a balance between different kinds of writing, just for my own interest. I think that I personally would get a little bored if I was only writing one type of writing all the time. So when I finish a book, usually I really like to work on something very very short. I enjoy that, you know, being able to write something, have it done quickly and move on from there. So it’s just a constant process, fine-tuning my schedule and my day, looking back to the things I’ve written and trying to figure out how I can move forward in a different way.

P: You’ve tried a bunch of media: blogs, journals and magazines (New York Times, National Geographic, Time, Scientific American, Science, and Popular Science), podcasts (Radiolab, Fresh Air, Meet the Scientist and This American Life), and recently video (STAT). Now that you have a broad image: what are the pros and cons of each medium ? Do you have a favorite and do you think there’s a shift from one to another of late?

CZ: I am working on a book right now about heredity and I really enjoy being able to just spend a whole day, or maybe even several days, just doing nothing but working on one particular big project. Creatively, that is really satisfying. But books are now in a very crowded landscape of media. This is not a bad thing but the fact is that people are reading and listening and watching science in lots of different ways and while I enjoy writing an old fashioned book on paper, I still want to be able to explore some of these other outlets. The video for STAT that I have been doing is totally new for me but I think that if you are lucky, what you do is that you try out these new things but you work with people that really know what they are doing, so you cannot make mistakes. In my case I am working with a producer named Matthew Orr, who has got 10 years of video experience, worked in places like the New York Times. So he and I, basically what we do, is that we just show up in laboratories, where people are doing interesting things, like stroke rehabilitation or hacking microbiomes or what have you. And we just basically take over and have them show us stuff and tell us their story and so on and Matt is filming all the time and looking for the beautiful images to complement what we are talking about. But this is a completely different challenge, you only got maybe 5 minutes to summarize what people have been doing for years, which is not always easy.

P: Alright. Do I still have time for a few questions ?

CZ: Yeah sure ! A few more minutes.

P: Inside the blogosphere, you’ve switched platforms at one point (Discover at first and now Phenomena for National Geographic). Can you tell us a bit about how you perceive those blog platforms, how they’ve evolved, what they offer to the bloggers, and so on ?

CZ: Actually there is a new book out called “Science Blogging: the Essential Guide“. It is published by Yale University Press and I have a chapter in there about the history of blogging. I guess because I am one of the old people now, who started blogging in the Jurassic. I actually started blogging on my own, on my own website, with some very primitive software, and then, a blog network called Courant asked if I would blog with them, and then I got invited to a larger blog network called ScienceBlogs, and then, from there, Discovery magazine, National Geographic. So blogging was very exciting. It is still very exciting, but there was a time in the early 2000’s, mid 2000’s even where there was just nothing else like it. Where you were you just able to write what you wanted, in your own way, you could integrate things like video and so on and just experiment. And respond quickly to readers and so on. And there are so many things that now we just take for granted in science media that really were being discovered for the first time with science blogging. Right now, I’ve put my blogging on hiatus for a while because I’ve got this book I am writing and I am also doing my stuff for STAT and writing a column for the New York Times, and sometimes I feel like my head is going to explode. I am going to get back to it. I still think that there is something about blogging that you just cannot do in other kind of formats.

A: Maybe quickfire questions and answers for your two last questions Pierre ?

P: Alright, so 2 last questions. At times, you’ve been on the forefront for advocating a new way of doing science, especially during the aftermath of the infamous Arsenic Bacteria discovery. Do you think this should be a job for people like you, with an external look on how science is made and perceived?

CZ: Well. What happened there was that Science magazine published a very high profile study by scientists funded by NASA claiming that they had found a really fundamentally new kind of life that could live of of arsenic, and use it to build DNA. And that would have been amazing if it were true, but it probably wasn’t. Really, I would not say that I was being an advocate there but I would say that I was writing about how the scientific community was receiving that and all the hype that went around it. And the fact is, that there were a lot of skeptics about it, and a lot of people who argued that, this was an example of a very flawed system for spreading scientific information, focused around very high profile journals, and it just wasn’t working. I was writing about things like post-publication peer-review, after papers come out, people should be able to still talk about it. I would not say that I’m being an advocate but I will say that I’m bringing to people’s attention a big trend in the scientific community, one that is just continuing to gain strength.

P: Alright. Can I..?

A: Yes, your very last one Pierre.

P: Alright. You’ve had quite a hard time explaining your fondness and awe about parasites to Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich on Radiolab. I am a fan of parasites and I’ve always wondered if this dialogue with those radiolab people was staged or genuine. Do you think you’ve contributed efficiently to the beautification of parasites?

CZ: Well, I do think that on Radiolab, Robert Krulwich and Jad Abumrad sometimes see it as their job to channel the reactions that lots of people have, to things like parasites ans so on, just like feeling that something is scary and weird and they do not want to know about it, it is just bad. And then it is up to people like me to persuade them that “No ! You should really give this some more thought, because actually nature is remarkable and surprising and beautiful, sometimes in a sinister way, but it is always something much more than you could have thought up on your own.” And if I can persuade them on the air, then hopefully some of the audience may come away as well with that similar kind of a change of view about how the World works.

A: So we don’t know exactly if it was staged or not but I guess this will do.

CZ: [Laughs] They did not send me any script. We just sat down and they would just start giving me hard time and… It’s fun !

P: It worked well.

A: It did ! Karim, do we have more questions from the chatroom ?

K: Yes, one last question from Alex. You mentioned that you were working on a book about heredity. Do you have any plans for other future books?

CZ: [laughs] No. Only in the sense that I have to get this book done before I can even begin to think about writing a another book. It is obviously a very big topic so all of my spare mental energy is going to working on this book. Once that is done, I’ll think about another one. Right now I am in the thick of it.

A: One project at a time I guess.

CZ: Yes

A: Ok. Now is the time for the quote. Did you do your homework ? Did you manage to come up with a quote in the meantime, Carl ?

CZ: I can certainly quote something from some of the things I written. There is one piece I wrote about hands in National Geographic. I was just trying to talk about the importance of the human hand to our evolution, our history and so on. The way I described it was: “The hand is where the mind meets the world”.

A: That is brilliant. An excellent thought for all of us to ponder on for next week. Fantastic, thank you so much.

CZ: Thank you.

A: Just remind us where we can find you on the world wide internet.

CZ: My web site is carlzimmer.com, carl with a “C”. My twitter is also @carlzimmer.

A: Brilliant thank you. And of course a planet of viruses can be found in all good bookshops and online and in 10 days exactly it will also be available in French under the title “Planète de virus”. I don’t know if I mentioned that it is an excellent translation.

A: Well is the time for goodbye. The pitch of next week: The next live session, next Tuesday (March 8, 2016), is a freestyle episode, with “Emile on bande”, a team of sociologists who reach out to the general public with comic strips. The freestyle episodes are our experimental format and we are going to try new things, as usual, especially regarding storytelling. Oh, and sorry for the English listeners… We’re switching back to French next week. Nobody’s perfect. This was our first show in English, and who knows, maybe it wasn’t the last one. Let us know how you feel about it and we will see what we can do. In any case, whether you liked it or not, feel free to spread the word. Any viral means will do. You can also love us on facebook, twitter, soundcloud, we’re all over the worldwide internet, actually.

A massive thank you to Carl Zimmer for being with us tonight, and a great big hug to all the team and to Karim, David and Pierre. Que servir la science soit votre joie.